Rats in the Walls

“Such secrets are not good for mankind.”

— H.P. Lovecraft, Rats in the Walls

Rats in the Walls (1924) was written during the height of Lovecraft’s publishing career and was published in Weird Tales. It is another direct link between Lovecraft & archaeology, and this one even has a full team of archaeologists attempting to excavate and explore the site of an old house. The story is one example of the link between Lovecraft & madness as well, as the main character ends up confined to a cell at “Hanwell” by the end of the story due to the experiences he had.

Again, madness in Lovecraft is a very different idea from that of mental health today. In this case, it is a clear link to the unknown and seeing a great, unspeakable horror that drives the narrator to the point where he is confined by the end of the book. “Hanwell” is a real insane asylum that has existed since 1831 and has undergone renovations and changes since then. Now it is known as St. Bernard’s Wing and is part of a larger hospital in Southhall, England, which is a city often incorporated into Greater London.

This story goes as follows:

The narrator, whose name is unknown but whose family name is Delapore (or de la Pore), describes an old estate known as Exham Priory that had been condemned and left to ruins after a tragedy left most of the inhabitants dead. The Priory became a place of wonder for antiquarians, who loved to examine the architecture. The architecture was said to span from pre-Roman builders up until the Gothic period.

Eventually, the narrator is told by his son more about the family legends while fighting in what would become World War I. The son’s friend, Captain Norrys, is the main source for these legends, and the narrator moves from America to the Priory to have it restored after his son passes away in the war. At this point, he learned that the Priory was believed to rest on a Druidical or pre-historic temple.

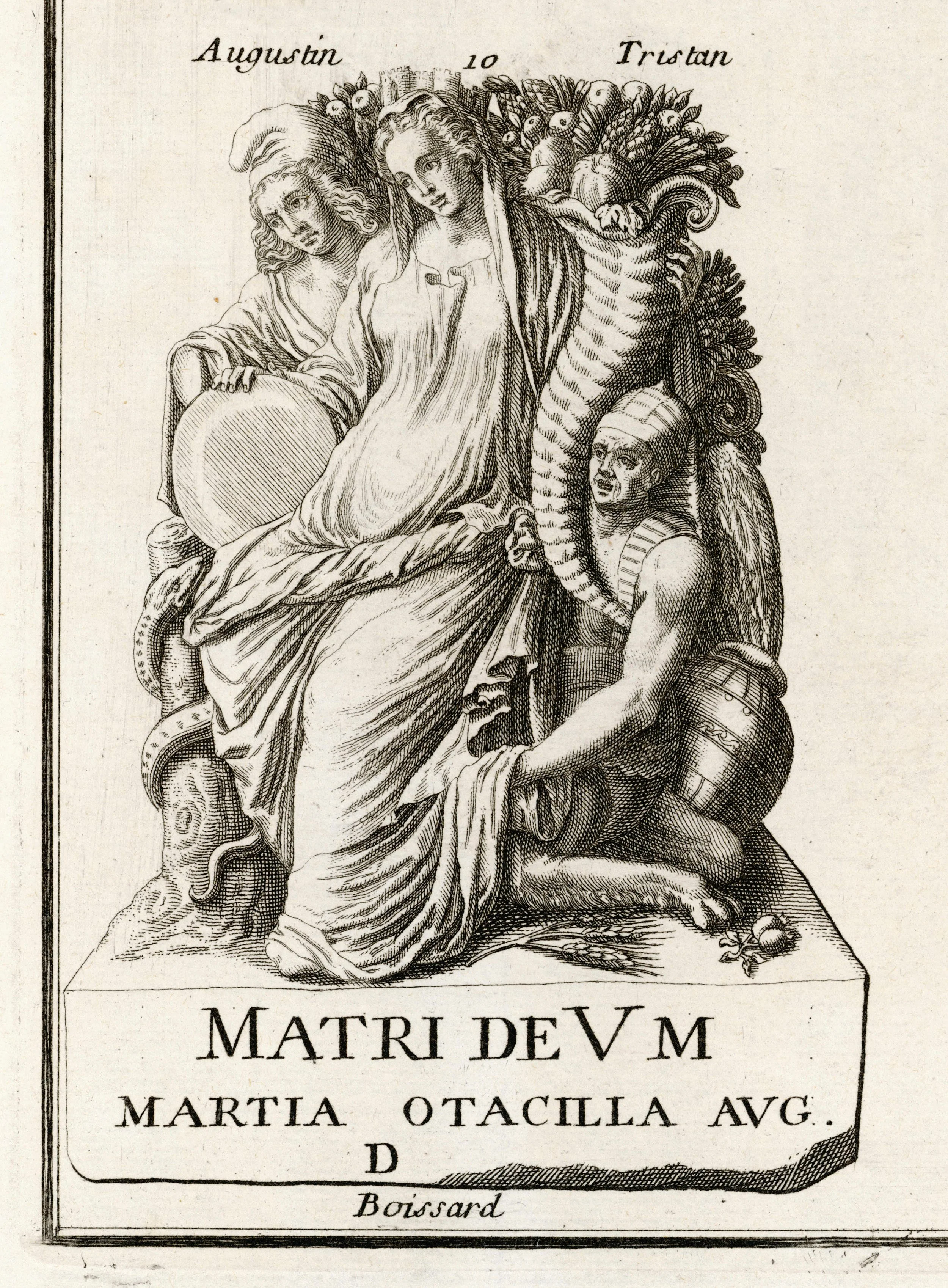

The previous occupants were called the “cursed of God” by the other locals and were speculated to be part of a cult of Cybele that formed around the Priory. It was then abandoned, but the moniker continued to follow the new occupants, including the narrator’s ancestors.

In between the previous narrative are anecdotes that support the idea of the villagers in the surrounding area being “too superstitious,” racism in the form of the narrator’s cat, references to African Americans in less-than-acceptable terms nowadays, as well as the “voodoo practices” that the villagers were involved in. The story was written in the 1920’s, but Lovecraft’s racism in this story cannot be excused just because he was “of the time,” as he was known to be an extremist even by his contemporaries. Unfortunately, this shows up in his work, and it is also present in archaeological practices of the time as well (See Trigger).

Meanwhile, the first hint of the titular rats comes about midway through the story when recalling the lore from the village that a swarm of rats once came from the Priory and consumed a fair amount of food and people. While the villagers are suspicious, Captain Norrys and the “antiquarians” are excited and want to uncover more.

After the house is restored, Captain Norrys and the narrator begin to notice the odd behavior of the cats, which all want to get to the sub-cellar of the Priory. This behavior is often accompanied by the sound of scurrying - as if there are rats in the walls despite it being a new renovation.

They find more evidence for the cult of Cybele and perhaps an even older cult, and the greed for knowledge of the past leads to the pair assembling a team of archaeologists -- who share this greed -- to uncover what awaits in the basement. They manage to move a stone altar and find a full world beneath the Priory, one filled with massive amounts of gnawed-on bones.

The bones found are examined by the archaeologists and said to be part of the “Piltdown man” class (See Fagan), but at the same time very human. These were mixed with bones of quadrupeds, and the reader is informed that there are secrets too terrible for mankind below. Some bones look slightly-more-human than a gorilla’s with “indescribable ideographic carvings” found in a prehistoric tumulus. At one point, the narrator describes the Priory as sharing a foundation with that of Stonehenge.

At the end, the narrator enters the vast darkness and flees after hearing certain sounds emanating from the scurrying rats, which he believes will lead him to the earth’s center, where a faceless god named Nyarlathotep waits. It is at this point that the narrator descends into “madness” mumbling about how it wasn’t him and the Latin phrases that were inscribed on the wall. He is found with the half-eaten body of Captain Norrys by the archaeologists, and the cat trying to attack him.

The archaeologists then, supposedly, blow up the Priory, take the cat away, and shut him in Hanwell while pretending the events that happened were something other than the truth. The story ends with the narrator insisting that it was the rats in the walls that did what they accuse him of.

Rats in the Walls, Antiquarianism & Insanity

Rats in the Walls is the story that deals directly with an excavation, as the antiquarians and the archaeologists are all excited to uncover and restore the house of the main character. We also see more examples of the locals knowing better than the group of greedy antiquarians, but this story highlights a couple of pseudological ideas that the other two stories do not.

The “Piltdown man” reference has been known to be a hoax for a long time now, one that is written extensively about in Feder’s Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. If you want a shorter breakdown, Stephanie Hall wrote an article for the Library of Congress that explains it well. However, Lovecraft directly references the Piltdown Man as the same evolutionary type as the bones he sees in the world beneath the Priory. There are other references to what are now known to be pseudoscience as well, and there are heavy-handed references to the cult of Cybele as well.

The cult of Cybele in real life was based around a Roman deity known as the Great Mother. Many Roman provinces that had a mother goddess often used Cybele as a stand-in for their own deities that the Romans forbade them from worshipping. This allowed them to still worship their deity while making it look like they were following the Roman Cybele. The cult has a lot of misinformation about it generally speaking. However, this idea of misunderstood religious practices being studied by archaeologists abounds in fiction like Rats in the Walls. You can also see this in less horror-like settings like the Indiana Jones franchise.

The ending of Indiana Jones & The Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). A good demonstration of knowledge costing sanity (& also life in this case).

The antiquarians are never described in great detail, only stated as excited to study the various time periods displayed in the Priory. However, this is often the case in a lot of media. There is usually a vaguely described archaeologist -- or curator, antiquarian, paleontologist, linguist, classicist, historian or even librarian that knows just enough about the past to be dangerous in these stories. They often serve as the ones to get the investigation rolling or are responsible for finding specific clues. They usually know incredibly obscure languages, and they have the translation skills of a minor deity. This may not be where the trope originated, but it is one that has stuck around and is certainly the case here.

Lastly, of the three works that have the most to do with archaeology, this one showcases the resulting insanity often seen in fiction the best. The way the narrator slowly falls into madness by continually hearing the scratching in the walls until he can’t help but descend into the space beneath the Priory has followed the Lovecraftian genre ever since. The quote, “Such secrets are not good for mankind” highlights exactly what it is that induces madness in archaeology.

It is not just that the antiquarians and the narrator are greedy, it is that some things are better left unsaid. This is the idea that the knowledge of ancient history is too dangerous for mortal ears. Insanity is the biggest trope across all of Lovecraftian horror, but it has made its way into archaeological tropes as well because of things like Rats in the Walls. Indiana Jones actually witnesses the consequences of mortals encountering too much knowledge at the end of his movies frequently. In Genesis, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil causes humans to experience death, so the idea of knowledge causing madness or death is not new. However, the incorporation of dangerous knowledge into modern pop culture was spread and distributed in large part by H.P. Lovecraft.

He was not the only one of his time who truly believed that too much knowledge was a bad thing, but he is the one who took it to the extreme due to his own prejudice.