Under the Pyramids lies a great mystery - one that still shapes Archaeological myth today.

Under the Pyramids, published in 1924 as “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs,” is one of the main sources that can easily link Lovecraft & Archaeology together. This work is a longer short story that was written as if from the perspective of Harry Houdini, so there is already a tie to the “supernatural” in the form of the real-life magician inserted into Egypt.

Harry Houdini would be dead less than two years after this was published in 1926, but he would have been at the height of his popularity during the time that this was written and published, having become the president of the oldest magic company in America, Martinka & Co. in 1923 and would have his own evening show a year later in 1925. Houdini remains in some way connected to Lovecraft because of this work, as can be seen in the game, The Last Case of Benedict Fox, where he is portrayed as the father-like figure to the protagonist.

“Mystery Attracts Mystery.”

— HP Lovecraft, Under the Pyramids

The following is the story of Under the Pyramids, summarized with emphasis on the points made about Ancient Egypt. There are quotes included with commentary from my peer and I, the former of whom has a Ph.D. in Archaeology, and who is referred to in the audio as “Seren.”

The story goes as follows:

In the first act, Harry Houdini arrives in Egypt, talking about the strange events surrounding his life and what happened in Egypt nearly fourteen years before. He spends the rest of the time narrating what happened, supposedly, speaking about his speculations on what he had read about Egyptology recently.

“What I saw - or thought I saw - certainly did not take place; but is rather to be viewed as a result of my then recent readings in Egyptology.”

Despite wanting to travel anonymously, he gave himself away by attempting to best a fellow musician on a trip on the Nile, before making his way to Cairo, at which point he meets a tour guide who is a thinly veiled stereotype of a Middle-Eastern tourist guide and who becomes a much bigger danger later. Houdini spends the rest of this act being guided around Cairo by this man and visits the Great Pyramids as well.

“This man, a shaven, peculiarly hollow-voiced, and relatively cleanly fellow who looked like a Pharoah and called himself ‘Abdul Reis el Drogman.’”

In due course, and after Houdini is told various things about “Egyptian magic” by the tour guide, he is captured and taken away alone in what was to be a test of his own magic powers to escape. Houdini is carried deep into the Pyramids, tied and lowered deep into a shaft, before he passes out amidst horrors that he seems unsure were of his own making or not.

“Egypt, he reminded me, is very old; and full of inner mysteries and antique powers not even conceivable to the experts of today.”

Act II retells Houdini’s attempts at escape. He first recalls the dreams he had while still unconscious, many of which involve the horror of Egypt’s antiquity, and the temples, Pharaohs, and other Great Beings of the time. As he wakes, he is not much better off, being consumed by thoughts of the dead and the terror of what lay beneath the Pyramids. He continues to lament that he knew anything at all of Egyptology, and that all the people of Egypt thought of was death and the dead.

“God!... If only I had not read so much Egyptology before coming to this land which is the fountain of all darkness and terror.”

He continues to describe this, while attempting to free himself of his bonds, which he does eventually do. He stumbles around this tomb, with only a matchbox to light his way, remarking occasionally that Archaeologists must not even know of this place, he thinks he might be in the bowels of the earth now. He hears a cacophony of marching feet and voices, which he attempts not to look at, but which have shadows of abnormal bodies - such as half-men, half-animal bodies.

“I saw that this was no part of Khephren’s gateway temple which tourists know, and it struck me that this particular hall might be unknown even to archaeologists...”

Houdini sees this mass was led by King Khephren, who he believes is the tour guide that had been leading them earlier and who succeeded in kidnapping him, and that they were all throwing sacrifices to some Unknown One that was concealed. Houdini sees a brief glimpse of it on his way out, describing it as a five-headed monster, which was what the Great Sphinx had been carved to resemble, before he escapes up the stairs and out into the desert in a hazy fog.

“The Great Sphinx!... what huge and loathsome abnormality was the Sphinx originally carven to represent?”

He is clearly disturbed by this event, but he pushes the thoughts of the horrors down with one simple line:

But I survived, and I know it was only a dream.

You can listen to the full podcast this audio was taken from on Podbean by clicking here.

Under the Pyramids, Egyptomania & Bad Stereotypes

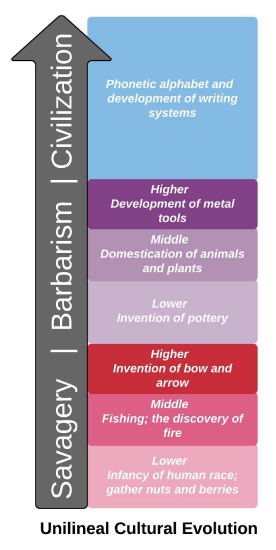

The main archaeological issue in this story is the dependence on the exoticism of Egypt and the people living there. At the time this story was originally published during, colonial and imperial views that archaeologists held put people who didn’t typically fit the European cultural model into the categories of Savages or Barbarians (see Trigger). While Egypt sort of got away from some of those views due to the “Classical” heritage it had, it didn’t get away from all of it.

Because Egypt had great pyramids and civilizations, it got incorporated into the Western model of civilization much the same way Greece and Rome did. Throughout history, the Western model typically inherited many of the ideas and traits from previous great civilizations. For instance, Rome imitated the empire of Alexander the Great and the Athenian city-state. Often, this was done to seem like one civilization “inherited” its culture and civilization from a previous one. Eventually, the British Empire associated itself with these great ancient civilizations in the same way to the extent that we now associate Imperial Rome with British accents in cinema, and Ancient Egypt is often incorporated into that same narrative (see Sumner and Aldrete).

However, the present inhabitants of Egypt in Lovecraft’s writing and in real life at the time, like Abdul in Under the Pyramids, were given stereotypes that would stick over time. In archaeological terms, indigenous populations of places like Egypt were seen as separate from their ancient kin who built the pyramids. This is due to the model of Darwinian archaeology where societies could only advance from Savagery to Civilization, and it is not seen as possible to “regress” (See the Unilineal Cultural Evolution chart to the right).

Lewis Henry Morgan, one of the sociologists responsible for this model. WikiCommons.

While this model is out of date and unused by the vast majority of archaeologists now, its effects on society stuck, whereupon the idea made its way into the greater popular culture through means like Lovecraft’s writings (and unfortunately, the education system). That said, the Nazi party did use archaeology to justify many of their radical ideas, which came to power not long after this story was published (see Arnold). Notably, they were not the only ones. These same ideas gave justification for Americans to “civilize” Indigenous populations, Western populations to justify slavery, and many other social injustices that have taken place since at least the 1600s, when the first “official” social anthropologists and archaeologists in the modern sense began to emerge. The Nazi party that rose up in the aftermath of WWI is simply the example everyone recognizes.

The character of Abdul presents a resounding example of this stereotype that shaped archaeology invading popular culture, as it had been for several hundred years at this point. However, while archaeologists have tried to move on, the stereotypes in pop culture remain in part due to the prevalence of these tropes.

Under The Pyramids also highlights the connection between the supernatural and archaeology, and it might even be a main part of the reason that those two get linked often. The idea of rituals, magic, and supernatural entities crossing paths while digging up ancient history is here to stay. Abdul is a practitioner of this magic, Houdini himself is a magician of a kind, and the inner workings of the Pyramid itself are home to a whole world of cult-like magic that the stereotyped locals are part of.

While cults exist in every corner of Lovecraft’s work and it is not new, the treatment of Abdul in light of this view of indigenous populations and Lovecraft’s own xenophobia puts a different spin on this story that is not present in either Rats in the Walls or At the Mountains of Madness.

Note: While called Darwinian archaeology or social Darwinism, the man himself didn’t have much to do with it. In fact, we don’t know what his ideas on the view would have been. Rather, other social scientists and archaeologists took his ideas and began applying them to human societies in a way that ultimately resulted in a lot of harm. These ideas of societal evolution are discussed as part of archaeological history but no longer supported by the archaeological community.

Next >>